The Value of SuperValu – Why Post Facto Defenses Can’t Erase Scienter

Table of Contents

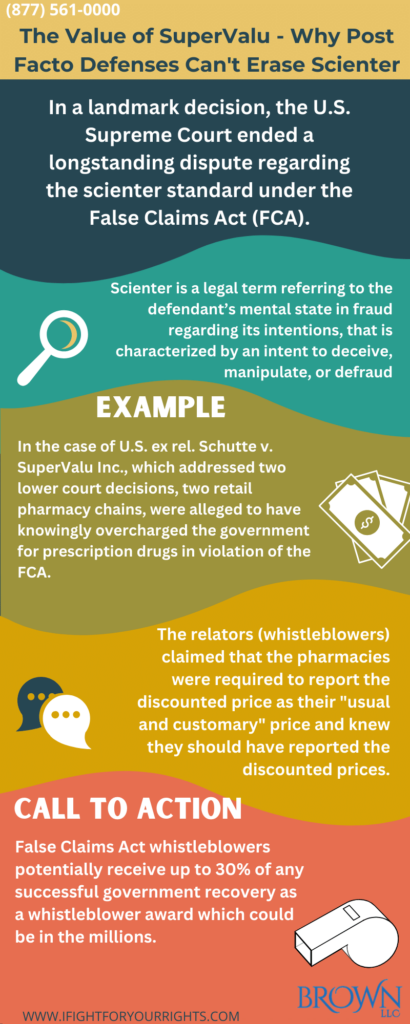

The U.S. Supreme Court recently delivered a landmark ruling that ends a longstanding dispute regarding the subjective versus objective standard for scienter under the False Claims Act (FCA). Scienter is a legal term referring to the defendant’s mental state in fraud regarding its intentions, that is characterized by an intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud. In the case of U.S. ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu Inc., which addressed two lower court decisions, the accused parties, two retail pharmacy chains, were alleged to have knowingly overcharged the government for prescription drugs in violation of the FCA. The FCA establishes liability for anyone who “knowingly presents, or causes to be presented, a false or fraudulent claim for payment or approval,” with “knowingly” defined as having (1) “actual knowledge” of the falsehood, (2) “deliberate ignorance of the truth,” or (3) “reckless disregard of the truth” (31 U.S.C. §3729).

The relators (whistleblowers) claimed that the pharmacies were required to report the discounted price as their “usual and customary” price and knew they should have reported the discounted prices. Their conscious knowledge that they were obligated to report it was an indication of their prospective liability. After they engaged in the alleged fraud, the False Claims Act defense lawyers later concocted an argument that their conduct was defensible if you examine certain regulations that they didn’t consider at the time. The lower courts upheld the post facto defense and decided that even though the Defendants evidenced scienter when making decisions, their scienter was trumped by the concocted defense arguments that they weren’t thinking at the time. In short, at the time they billed the government they thought they were defrauding the government, and the courts thought the evidence of bad intent was not enough for the case to proceed.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, firmly rejected the Seventh Circuit’s interpretation. The Court emphasized that what truly matters in an FCA case is whether the defendant knew the claim was false. In the Court’s view, the FCA’s scienter element focuses on knowledge and subjective beliefs, not on what an objectively reasonable person may have known or believed. The Court also clarified that the analysis of the knowledge element should primarily concentrate on what the defendants thought and believed when they submitted the false claims, rather than their post-submission thoughts or interpretations that might have made the claims appear accurate. Justice Thomas wrote, “What matters for an FCA case is whether the defendant knew the claim was false. Thus, if respondents correctly interpreted the relevant phrase and believed their claims were false, then they could have known their claims were false.”

The Court introduced an expanded definition of the “reckless disregard” standard, capturing defendants who were aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that their claims were false but submitted them anyway. This expanded standard allows the FCA to reach defendants who knew their submitted claims were fraudulent, even if they later provided an “objectively reasonable” interpretation of a requirement material to the government’s payment decision.

Although the Court clarified the scienter standard, Justice Thomas’s opinion had some consolation dicta for FCA defendants. The opinion recognized that a good faith, albeit mistaken, interpretation of the terms related to the decision to pay might serve as a defense against FCA liability based on knowledge.

This Supreme Court decision will have a far-reaching impact on future FCA cases, in which defendants have echoed thoughts and beliefs that their conduct was wrong concurrently with them submitting claims to the federal government. Defendants can no longer hire some of the best whistleblower law firms for defense to fabricate an interpretation after the fact that didn’t exist at the time of the decision-making and use that post facto defense as a basis for dismissal. The guilty intent at the time appears to be enough to continue with the False Claims Act case past the motion to dismiss stage. For guidance on choosing experienced representation in these cases, see our guide on selecting the best False Claims Act lawyer.

Speak with the Lawyers at Brown, LLC Today!

Over 100 million in judgments and settlements trials in state and federal courts. We fight for maximum damage and results.

Breaking down SuperValu even further

The federal government is entitled to pricing that is not inferior to the private sector. As one of the biggest payors, if the government was consciously negotiating contract prices it would probably broker closer to the best pricing, but the government does not have the bandwidth to do this. Instead, when certifying compliance with participation in programs like Medicare and Medicaid, the certifier indicates they are giving the government pricing comparable to the private sector. Things become trickier when things are opaque. That is, while the government appears to be receiving the same pricing, unbeknownst to the government, the companies are giving a 10% rebate on the pricing. For example, let’s say a pharmacy is charging the federal government and private insurance alike $10 a bottle for penicillin, it seems the pricing is the same, especially if the company is certifying the pricing is the same and the rate sheet shows it’s the same, but unbeknownst to the federal government, if the private insurance is receiving a 50% rebate after payment, its true cost is $5 per bottle which means the government is paying an extra $5 per bottle more.

If when the company is submitting the claims to Medicare they believe they are defrauding Medicare by charging $10 a bottle instead of the $5, then the fact that they believe it was a fraud is relevant and goes towards scienter. If after committing what they believe is fraud for many years they hire one of the whistleblower law firms that defends Medicare fraud with the firm structuring a defense that even though their conduct was wrong, that there was some information that had they known at the time would make the submission a good faith one, they can’t retroactively change the intent from bad to good.

So there is value in SuperValu showing that you can’t retroactively install good motives when there were demonstrably bad ones. The good motives that often expose these schemes are from whistleblowers coming forward under the False Claims Act to expose the plot and in turn receive a portion of the pot if they are successful.